Education Advisory Board (EAB)

Higher Education Research Cycle 2017

Advancement Team

Project: Mid-Level Giving at Universities

Setting the stage: My manager, Jeff Martin, and I began the six-month 2017 research cycle with a focus area: we wanted to create products that would help universities develop their major gift pipeline, or elevate mid-level donations to major donations—a figure that varies by school from $50K all the way up to $1M.

Ultimately, we sought to create a valuable study we would present to paying members so they could level up their advancement shops, as well as a number of accompanying deliverable that would provide impact: webinars, white papers, blog posts, infographics, and a problem diagnosis tool.

Literature review: First, we wanted to understand what the broader fundraising community had to say about major gifts. This meant that we needed to dig into peer-reviewed research, magazines, newspapers, and material produced by our consulting competitors, such as BlackBaud.

I owned our lit review and performed it via research databases and the Evernote platform. At the end of a month-long pull, I wrote a summary document that you can view at the left.

Scoping: Next, we needed define our specific project roadmap in the broad terrain of major gifts. What research question could we answer that would uncover tactics to help all of our clients grow their number of big donations?

To solve this problem, we performed root-cause analysis through a mixture of interview and contextual inquiry research. I talked one-on-one with advancement executives about their biggest successes and pain points. I also observed clients walk through their daily activities.

By using Excel to group challenge areas into buckets, our analysis showed that the root cause of the major-gift problem was that gift officers juggled too many identified prospects and needed to be able to go through them faster. Our research question transformed into how to help them do just that.

Click on the document at the right to view one of my notes summarizing an hour-long interview call.

Project kickoff: With our question defined, we moved to formally kick off our research project. We met with other members of the Advancement team to pitch our ideas and gather their feedback.

During our project kickoff, we presented a document that I drafted. It explained the process we had gone through to narrow down our research question, define our main problem, and set A to B goals.

You can view this document at the left.

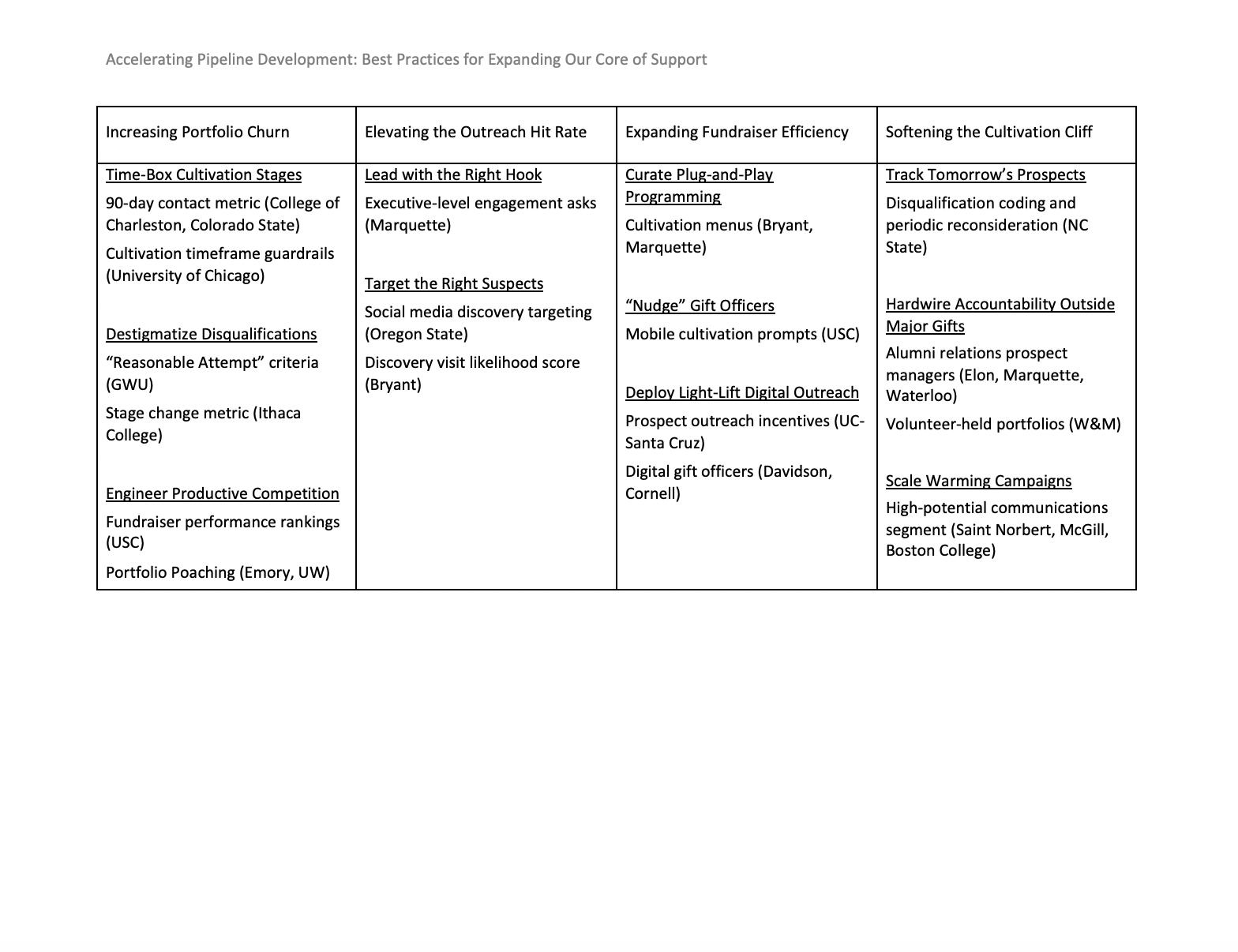

Checkpoints: After kickoff, it was time to continue our research along a set of refined questions.

Advancement executives told us that their major gift officers weren’t qualifying prospects. By watching gift officers work through their portfolios, we learned that their challenges could be grouped into four categories: they were not throwing bad prospective donors out of their portfolios to focus on promising ones, they were ineffectively sending the same outreach to everyone, they needed help with scaling digital messaging, and they lacked solid communication channels among themselves.

We carried out four checkpoints along the length of our research cycle to make sure that we were able to define each of these categories and come up with good strategies to

address them.

You can find one of our checkpoint

flowcharts to the right.

Study: As we assembled our research into a long-form study, we realized that our focus on gift officers was not the best organizing architecture because it did not speak to our clients’ most basic experience.

All universities have different advancement office structures: some have designated gift officers assigned to annual gifts, mid-level gifts, major gifts, and corporate gifts, some have gift officers that do all four, some include the university president, and some don’t.

Because of these disparities, we decided to retune our study organization to focus on donors themselves: how can we adjust portfolios to make sure assigned prospects are taken care of, unassigned high-potential prospects are seen, and tomorrow’s high-potential prospects start a giving relationship with the university?

This adjustment more directly answered what advancement executives really meant they told us their gift officers were slow: How do we make sure that we do not miss out on any major gifts?

The study is member-only content protected by a paywall. View its landing page on the right.

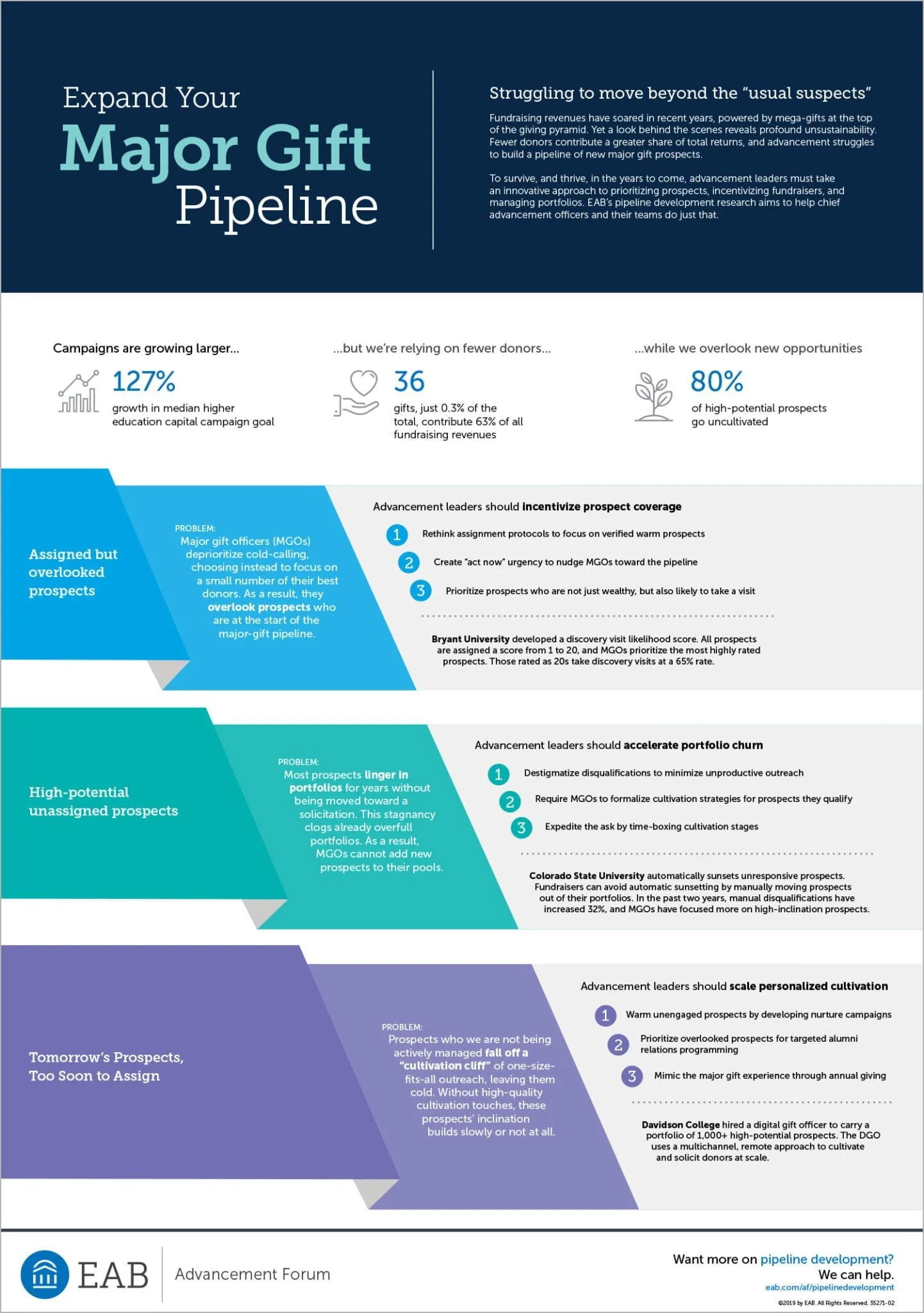

Infographic and blog: Not everyone has time to read a whole study, especially busy executives. People want actionable insights that they can apply immediately. Also, we don’t offer our long-form content for free, so it can’t be used for marketing purposes.

We used short-from deliverables, like an infographic and blog posts, to fix both of these problems. They took bite-sized, important pieces of information we uncovered throughout our research and presented them in compelling ways to two audiences: clients who wondered if the long-form study and in-person presentations were worth their time and potential clients who wondered if buying a membership to our advancement research program was worth their money.

I wrote the blog post text myself, which my manager then edited before web editors published it under his name.

For the infographic to the left, I worked with graphic and content designers to tell the story of our research through simple language and visuals. Because I had worked as a web editor in the same company before, I was more involved in this process than other research analysts.

University of Pittsburgh

Department of Hispanic Languages and Literatures

Institute for International Studies

Dissertation: Invented Indians, or White Delusion, Make-Believe, and Native Mobilization of the Colonial Imaginary in Sixteenth and Seventeenth-Century Mexico

Setting the stage: In academia, I identified a problem with how we talk about Native peoples and power. Academics—heavily influenced by Michael Foucault and his idea of biopower—frame power as pervasive, all-knowing, and controlling of everyday life. As a result, we talk about Native peoples as victims of power.

I analyzed the primary and secondary archive of the conquest of Mexico, one of the most well-known and visceral displays of colonial power, and I found no data to support this assumption. Instead, critical race theory headed by Black and Native thinkers helped me understand these encounters very differently: as a delusive attempt to create a supremacist identity and ignore all lived reality that disproved supremacy.

In academia, we were echoing the colonizers’ own beliefs about themselves—not what really happened.

Literature review: I synthesized two main bodies of work for my literature review. The first included primary documents that described Native peoples and the conquest of Mexico—first-person chronicles of Native and Spanish writers who had been there. The second was made up of secondary academic literature written about the conquest and colonization of Mexico, as well as critical race theory that helped me build my theoretical framework.

Using Excel and writing document summary notes, I kept track of Spanish, English, Latin, and Nahuatl-language texts, written over a period of several centuries and for many different purposes: evangelical, historical, legal, and academic. I read long and convoluted colonial court cases, sixteenth-century Nahuatl-language histories, and the most recent books written by well-known scholars like José Rabasa Native-history specialist Paige Raibmon, who sits on my dissertation committee.

My literature review gave me an opportunity to learn how to synthesize mounds of information and pull out parts that matter.

See one of my summary notes on the right.

Scoping: After using my literature review to organize data about Native peoples and the conquest of Mexico, I connected between data points to create a specific research question. How did the conquest and early colonization of Mexico depend on made-up images of Europeans and of Native peoples, and how did Native individuals use these made-up images to survive, create, and access power?

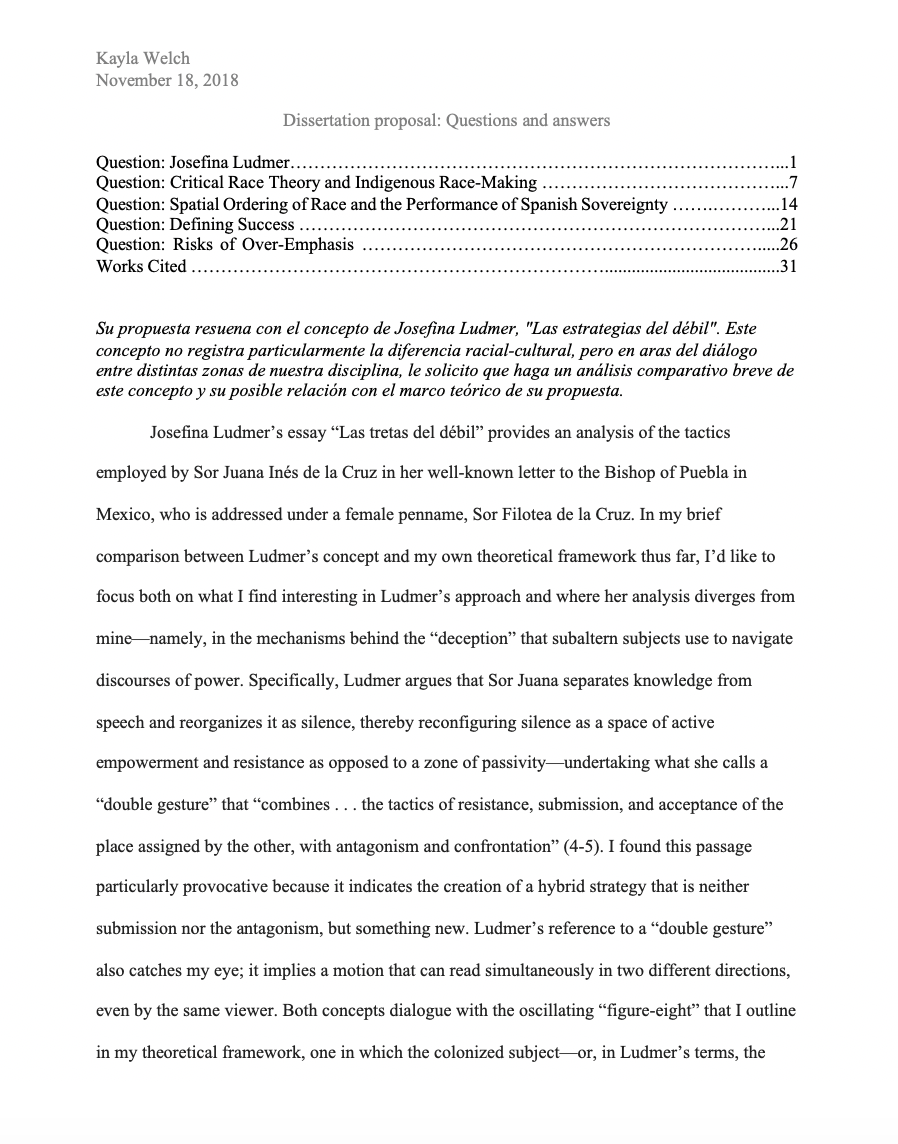

Checkpoints: To continuously refine my work, I settled on a series of checkpoints that would ensure I was on the right track and creating a cohesive project. The most important of these was my dissertation proposal defense. I had to put together a thesis committee who would oversee my work and get their approval before I could continue with my project.

I interviewed experts across the world and explained my proposed work to them. Once I assembled my committee, I sent them my proposal. They sent me back a written list of questions related to their expertise, and I had two weeks to satisfactory answer them before my verbal defense. I researched new texts and used them to change and strengthen my ideas where needed.

View the document containing my committee’s questions and my answers to the left.

Research communication: As I developed my project, I communicated my results to committees and groups of my peers.

I was nominated for and won the Andrew Mellon Pre-Doctoral Fellowship, a prestigious research fellowship offered to a select group of graduate students across the sciences, humanities, and arts. I also participated in peer conferences in New York, Colombia, France, and Peru.

You can see my fellowship research statement and my accepted presentation for the 2020 International Linguistics Association (ILA) conference to the right.

Results: As I continued to develop my project in the light of emerging evidence, I settled on three case studies, or what I referred to as “microhistories,” to answer my research question: a Nahua writer who edited Spanish chronicles about the conquest, a group of Maya nobles who pretended to have committed idolatry and handed over made-up idols in order to avoid torture and execution, and Zapotec men who pretended that their Native rivals had sacrificed human beings to make them targets of Spanish force. These three case studies made use of three made-up images of Natives that Europeans relied upon in order to prove their supremacy.

I completed my three chapters, introduction, and conclusions, and I am currently scheduling my thesis defense.

View my third chapter draft to the left.

University of Pittsburgh

Department of Hispanic Languages and Literatures

Institute for International Studies Social and Public Policy Conference (2019)

Project: A comparative analysis of Indigenous-oriented education policy in

Mexico and Guatemala

Setting the stage: At the University of Pittsburgh, I specialize in the cultural representation and political participation of Native communities in Mexico. While narrowing the scope of my dissertation, I pulled statistics from Mexico’s reports on national development that demonstrated how badly the educational system was failing its Native inhabitants: despite more investments, greater access, even less Native people were graduating high school than 20 years ago. I saw that Guatemala showed similar data. I performed a comparative analysis between the two systems to identify root causes of system failure.

Literature review: I performed a literature review to understand what the academic and policy communities had written on education and Native populations in Mexico and Guatemala. I then created an annotated bibliography of the most useful sources, which included primary material, secondary material, and statistical data published by federal and local governments. My biggest takeaway was that the subject remained largely untouched: I found research that analyzed education systems and research that analyzed Native groups, but not both.

Look at my annotated bibliography to the right.

Scoping: After organizing my data into problem areas, I realized that the research I faced was one of contradiction. Both Mexico and Guatemala had begun the twenty-first century with a focus on the preservation and education of Native communities, but graduation rates and Native linguistic loss were rapidly accelerating.

This was the interesting question: why did similar discourse and similar data not match in both cases?

These congruencies led me to hypothesize that the systematic root cause had to be international. Look below to view Spanish-language visual representations of data that I created in Excel and PowerPoint to allow me to identify data patterns.

school enrollment data of mexican Indigenous population over time

Educational attainment data of guatemala’s indigenous vs. non-indigenous populations

Linguistic, literary, and educational attainment data of mexico’s indigenous population over time

Checkpoints: I had defined my research question to international systematic failures of of Indigenous-oriented education policies. I then analyzed different international actors and forces and discovered that the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Bank, and USAID had granted and loaned millions of dollars to both Mexico and Guatemala in the 1990s and early 2000s with the goal of decentralizing education systems, especially in majority-Native areas.

This allowed me to identify the root cause of international systematic failure: international diffusion of neoliberal multiculturalism. You can see the paper outline I created as a checkpoint to the left.

Study: My final study argued that the diffusion of neoliberal multiculturalism and the resultant decentralization of government had systematically failed to improve Native educational outcomes in both Mexico and Guatemala.

I argued that the data revealed six policy improvements to better these outcomes, including the clear definition of policy objectives; the development of wide-scale data gathering initiatives, the teaching of Native languages to all Mexican and Guatemalan students, including non-Native students, and the creation of bridge programs to help Native teachers receive federal teaching certifications.

You can find the study to the right.